REPORT: Comics Fandom Gets “Super”sized With a Serious Museum Show

By Adam McGovern

(Adam McGovern writes for the TwoMorrows mags, Comicon.com/PULSE and ComicCritique.com in addition to ComicList. He is an accomplished speaker on comics at cons and museums, and [with artist Paolo Leandri] co-created the Ignatz-nominated comic Dr. Id, Psychologist of the Supernatural.)

An eight-foot-tall Spider-Man sculpture looms over you while colorful covers compete for your attention. A how-to video on cartooning loops while crowds form around original art pages. A visit to your local comics emporium? No, an afternoon at New Jersey’s Montclair Art Museum, where comics and culture clash and join forces in the exhibition Reflecting Culture: The Evolution of American Comic Book Superheroes, on view through January 13, 2008.

The opening day was mobbed with fanboys and girls of all ages and walks of life (and no doubt many other visitors who were just curious about the strange ongoing phenomenon of these spandex gods and warriors and their hold on the mass-media imagination). There have been shows about the art of comics (like the traveling Masters of American Comics last year), but this is the most extensive exhibition yet of comics-as-art -- featuring good amounts of original pages like the earlier show but mostly relying on the comics themselves as touchstones of what was on Americans’ minds across eight decades (from the Great Depression to 9/11).

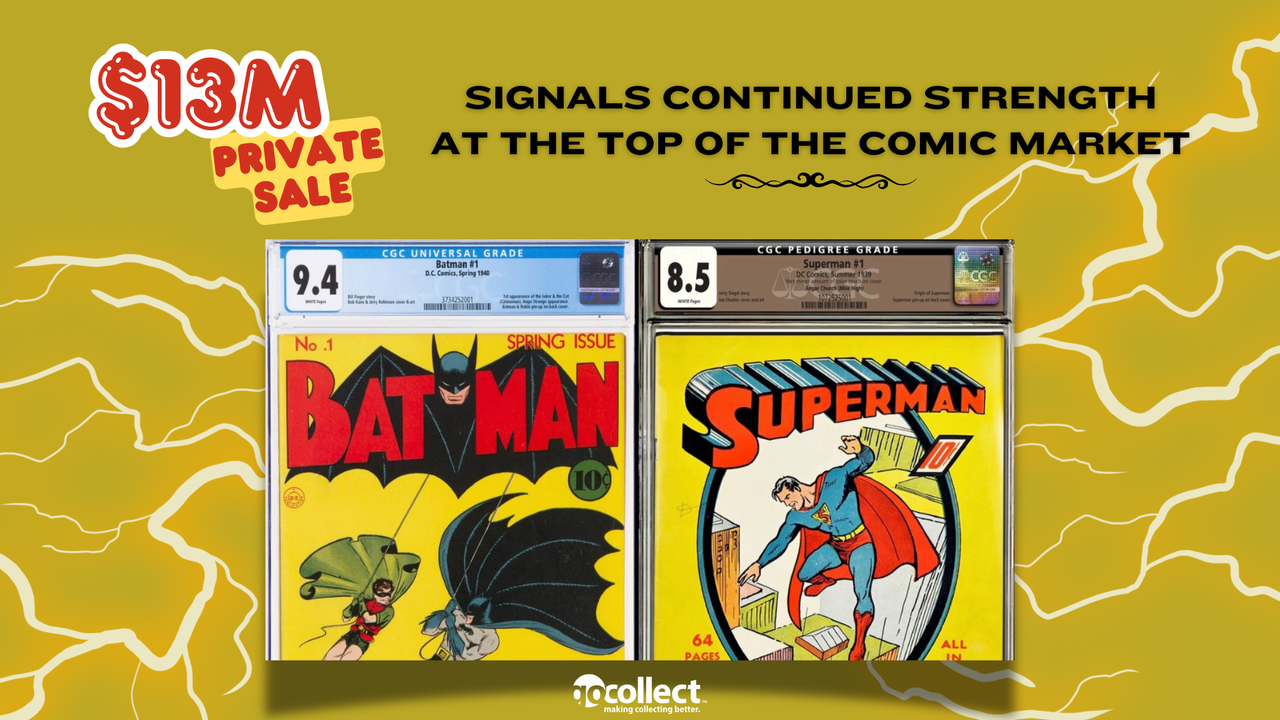

Longtime comics fans will thrill to see the hallowed relics of pop in person -- all the auction-house champions are here, from the first Superman and Batman appearances onward -- while viewers new to comics will appreciate a scholarly but conversational narrative that runs next to all the specimens.

The familiar trends are covered -- Captain America confronting Hitler and multiple heroes contending with anxiety over possible nuclear war -- as well as major phases you’ve forgotten about your own favorite heroes, like Superman’s pre-WWII role as an avenger for the common man and woman, battling unscrupulous Wall Street types in stories like “The Economic Enemy.”

You’ll see interesting comments from the creators themselves, like Jack Kirby’s remark that the first Captain America comic “was meant to look more like a movie than a traditional comic book” -- a prescient example of comics being aware of their competition with moving media (from Hollywood to Wii).

And you’ll encounter many interesting takes on the comics you thought you knew all about from curator Gail Stavitsky’s insightful text. She traces the development of superteams like the 1940s Justice Society to the group endeavor and social unity needed for the war effort of the time (not just the commercial objective of stuffing together popular superheroes that seems most obvious). And a seemingly simple statement -- that Spider-Man became “the most widely-imitated superhero archetype since Superman” -- gets at an important and overlooked truth: that the example set by these characters has to do with the values of their times (invincible self-confidence for Superman’s greatest-generation roots; vulnerable uncertainty for Spidey’s countercultural era), and not just their sets of powers (since, while every Superman follower, like Supreme and Prime, is clearly a clone of his style and abilities, there aren’t many other neurotic insect heroes but Spidey’s attitude is just as influential).

The show takes a good art-historical look at the mechanics of comics, with clear structural analysis of how suspense and action are built through scene and page composition, and how the demands of deadlines caused artists to evolve shorthand styles that showed the essence of emotions and the fast-paced basics of movement (this is especially a theme in a companion show spotlighting three New Jersey-based comic-art heroes: Joe, Adam and Andy Kubert).

Any exhibit like this is bound to stir some fan debate. For instance, the Silver Age Flash’s origin in a chemical accident is said to be an example of anxieties over out-of-control science in the cold war, though it seems more a demonstration of how such accidents in pro-establishment DC comics produced optimistic golden-boy heroes like the Flash while they resulted in monsters like the Hulk over at more-iconoclastic Marvel, an important difference in the Big Two’s levels of trust in “the experts.” And a section on Native American heroes singles out Scalped (nor even a superhero comic) as stereotypical when to this writer it seems merely unsanitized (with deep moral shadings to even its most antisocial characters). But that’s just another way in which this show stimulates thought and proves that comics are worth discussing.

Reflecting Culture covers a staggering amount of history with a sharp instinct for the highlights, identifying the major movements without ever treating things in too broad strokes. To give visitors the clearest view of the shape comics history has taken, this means, for instance, that Captain America’s evolving role as a super-patriot gets extensive space and Sub-Mariner’s as a super-insurgent gets none, since the former is much more well-known and ultimately more influential (though the latter is just as interesting for its political implications and pop oddity). But this very show is what makes future ones focusing on specific comics eras and themes seem possible, with this one setting the scene and establishing the validity in a groundbreaking way.

The museum has many activities (and rotating companion exhibits, including some monumental murals by Greg Hildebrandt) planned through mid-January of 2008; these have already included a panel discussion with famous comic writers, a day of Halloween superhero costume fun, and even a mini-con (at which -- full disclosure -- I gave a gallery lecture), with events like a December talk by leading filmmaker and Black Panther scripter Reginald Hudlin still to come. There’s a thrilling saga for the scholarly realm starting here, and if you’re anywhere near New Jersey you don’t want to miss the origin story the Montclair Art Museum has set forth.