Step into my office, wiseguy, and let me lay it on you straight.

There's a certain kind of magic that flickers in the world of private eyes—a magic that’s been alive and kicking since the days of the earliest pulp magazines. If you’ve ever wondered why so many folks dream of donning a fedora and trench coat, solving gritty crimes, and playing by their own rules - look no further.

Today we're going to peer into a steely lifestyle that’s as compelling today as it was a hundred years ago.

The Genesis: Pulp Magazines

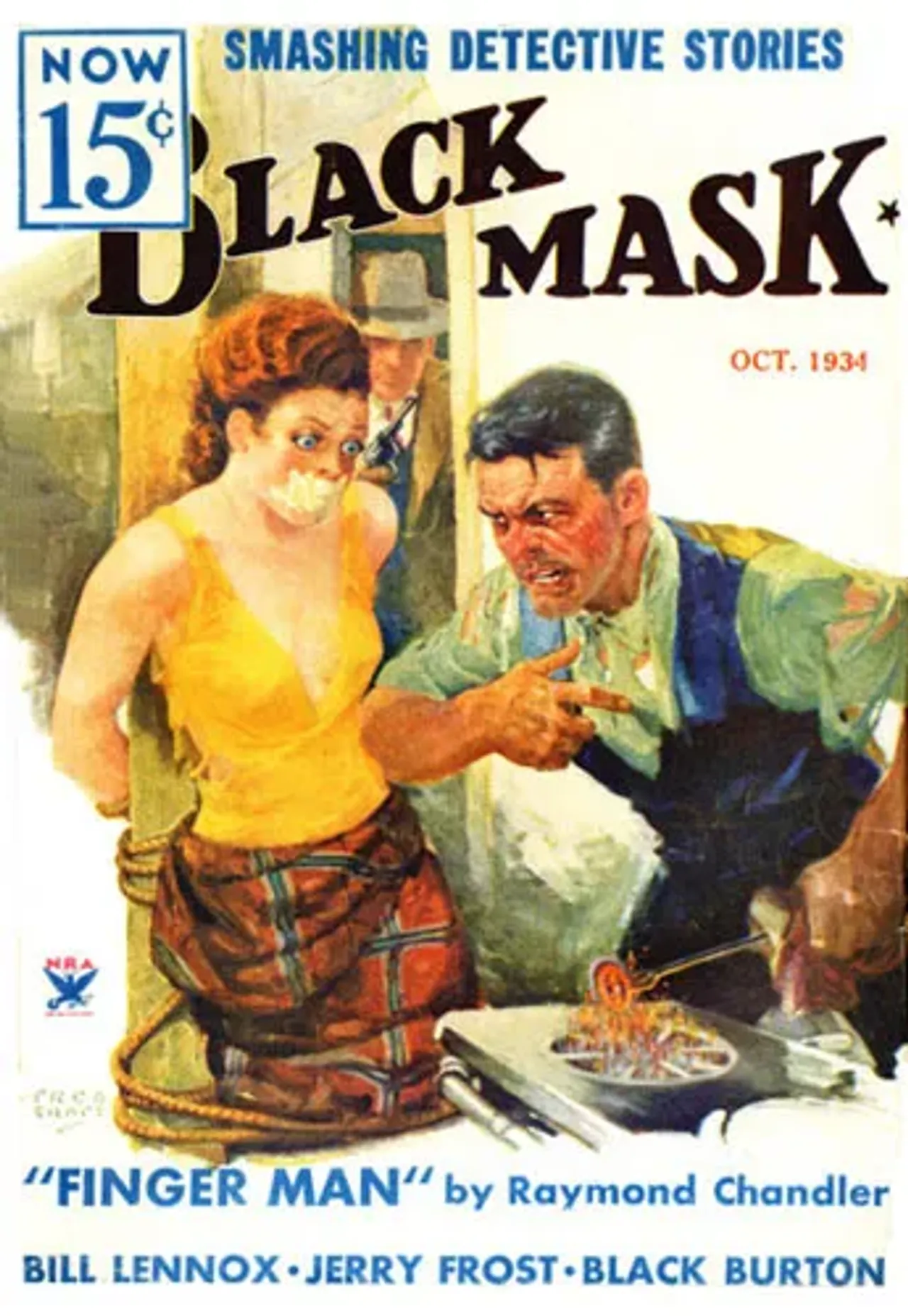

Let’s rewind the tape to the roaring twenties and thirties. The air was thick with the smell of cigarette smoke and the sound of typewriters clacking away on pulp magazines. These slick, dime-store delights were bursting with tales of adventure and crime, and they didn’t shy away from the seedy underbelly of society. The private eye was born in this rough-and-tumble world. A hero who didn’t follow the rulebook but wrote his own.

In those days, the detective’s charm wasn’t just in solving cases; it was in the gritty dialogue, the morally murky waters, and the sheer audacity of these lone wolves. These detectives thrived in a world where the lines between right and wrong were as gray as the city streets they prowled. Often, the only color present in this bleak climate was painted on the flimsy covers that overhung the cheap paper they existed upon.

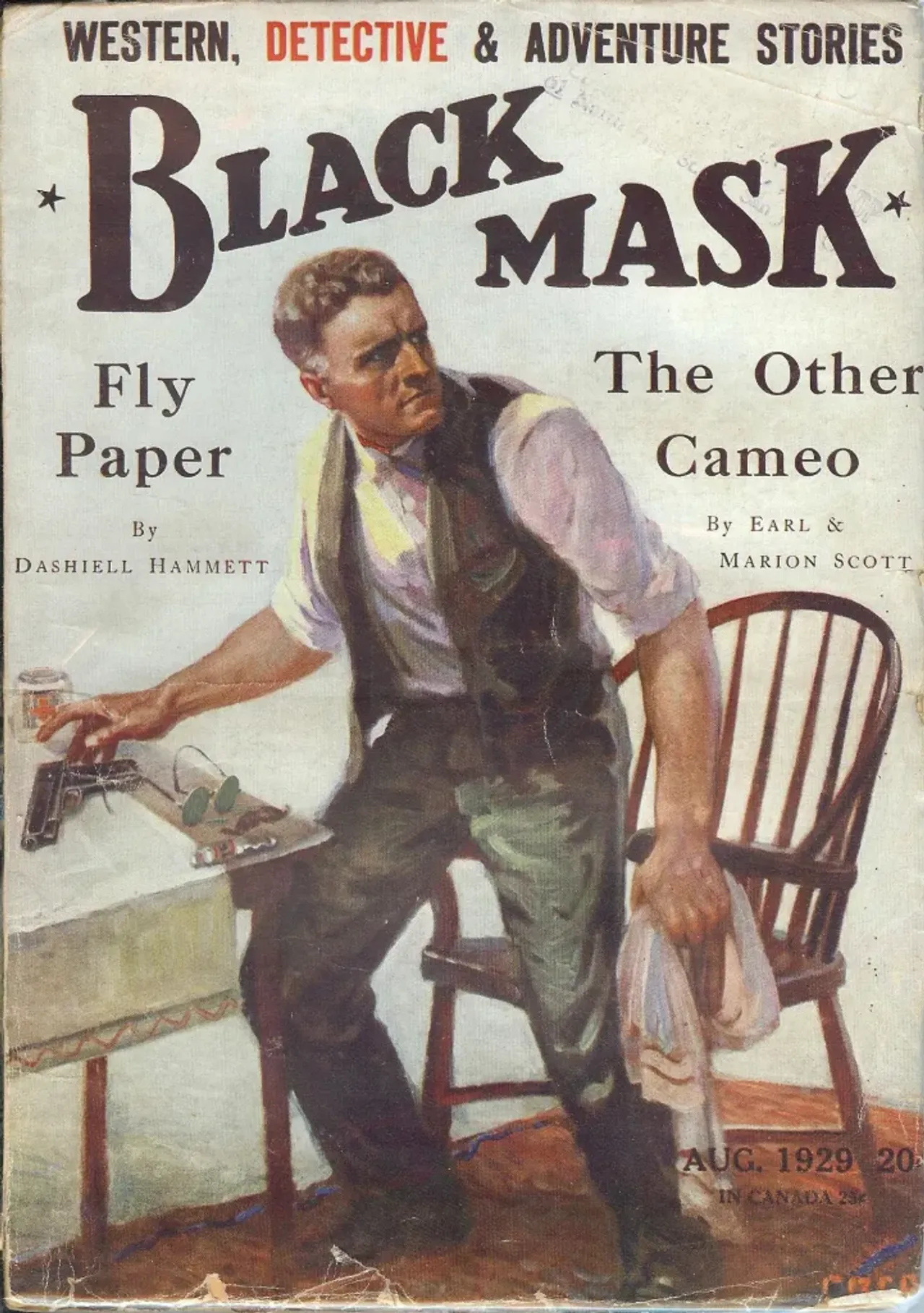

Dashiell Hammett is credited with kick-starting what is known as the hard-boiled genre with his seminal story "Fly Paper" in Black Mask magazine.

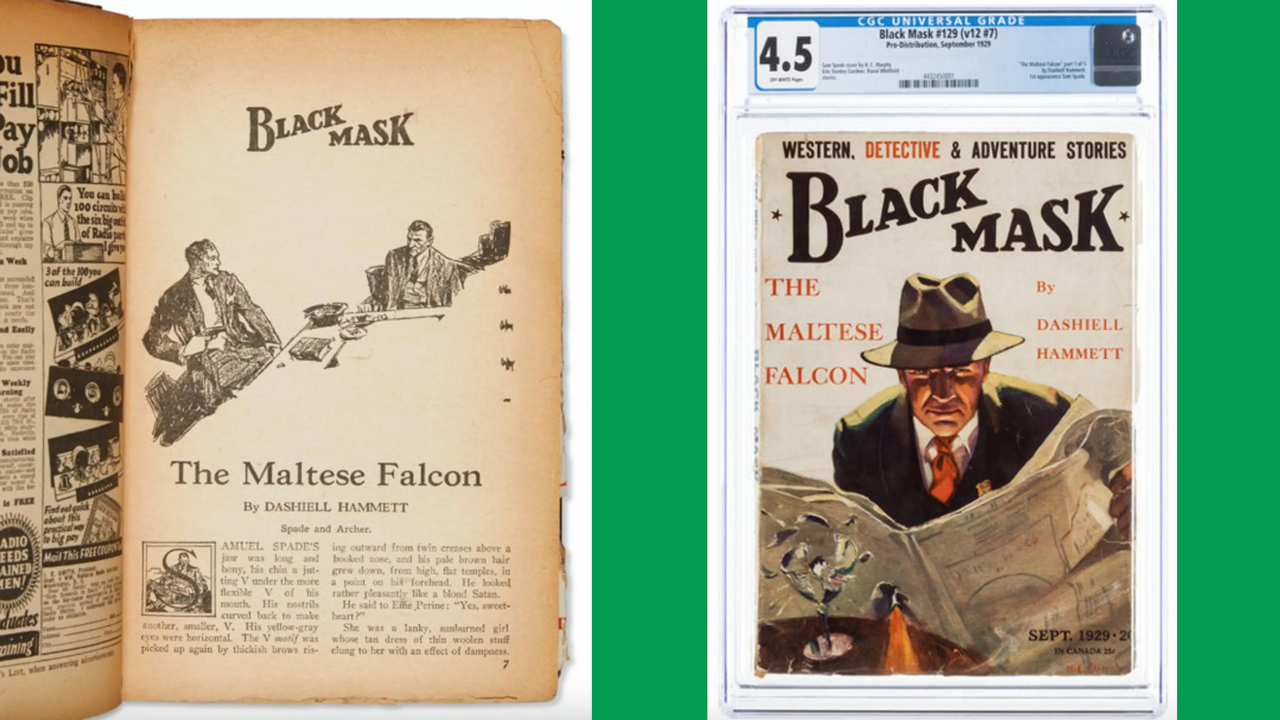

Just one month later, Hammett would introduce the world to one of the greatest all-time capers -The Maltese Falcon - and one of the greatest hard-boiled detectives - Sam Spade - over a 5-issue run in Black Mask from September 1929 to January 1930, before the entire story was published in novel-length form the following month.

Hammett had cut his teeth as a private detective himself before turning to writing, crafting gritty, atmospheric tales that peeled back the grime of urban life. One can only imagine then from where he drew his influence when creating works like Falcon and The Thin Man, which set the gold standard for crime fiction. With a knack for creating tension and a flair for dialogue, Hammett’s stories remain a cornerstone of noir literature and a profound influence on the detective genre.

The Prototype: Elementary Evil

It's important to understand that before the pulps would unlock the gritty world of case-hardened detectives, there was one man who stood as the quintessential model of what a sleuth should be: Sherlock Holmes. Created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in the late 19th century, Holmes set the standard for detective fiction with his razor-sharp intellect, his ultra-methodical approach, and a personal code of conduct that emphasized rationality over brutality.

Holmes was a paragon of reason and logic. His methods revolved around observation and deduction, solving crimes as if they were intricate puzzles to be pieced together rather than brute-force confrontations. While the detectives of the pulp era would often navigate the murky waters of moral ambiguity and operate outside the law, Holmes upheld a strict ethical code. He sought truth and justice with a commitment that stood in sharp relief to the often cynical, jaded attitudes of later detectives like Sam Spade or Philip Marlowe.

While pulp detectives wrestled with the gritty realities of urban life, Holmes moved through the fog of Victorian London with a sense of poise and decorum. His reliance on intellect over violence created a clear distinction between the cerebral sleuth and the action-driven heroes of the pulps.

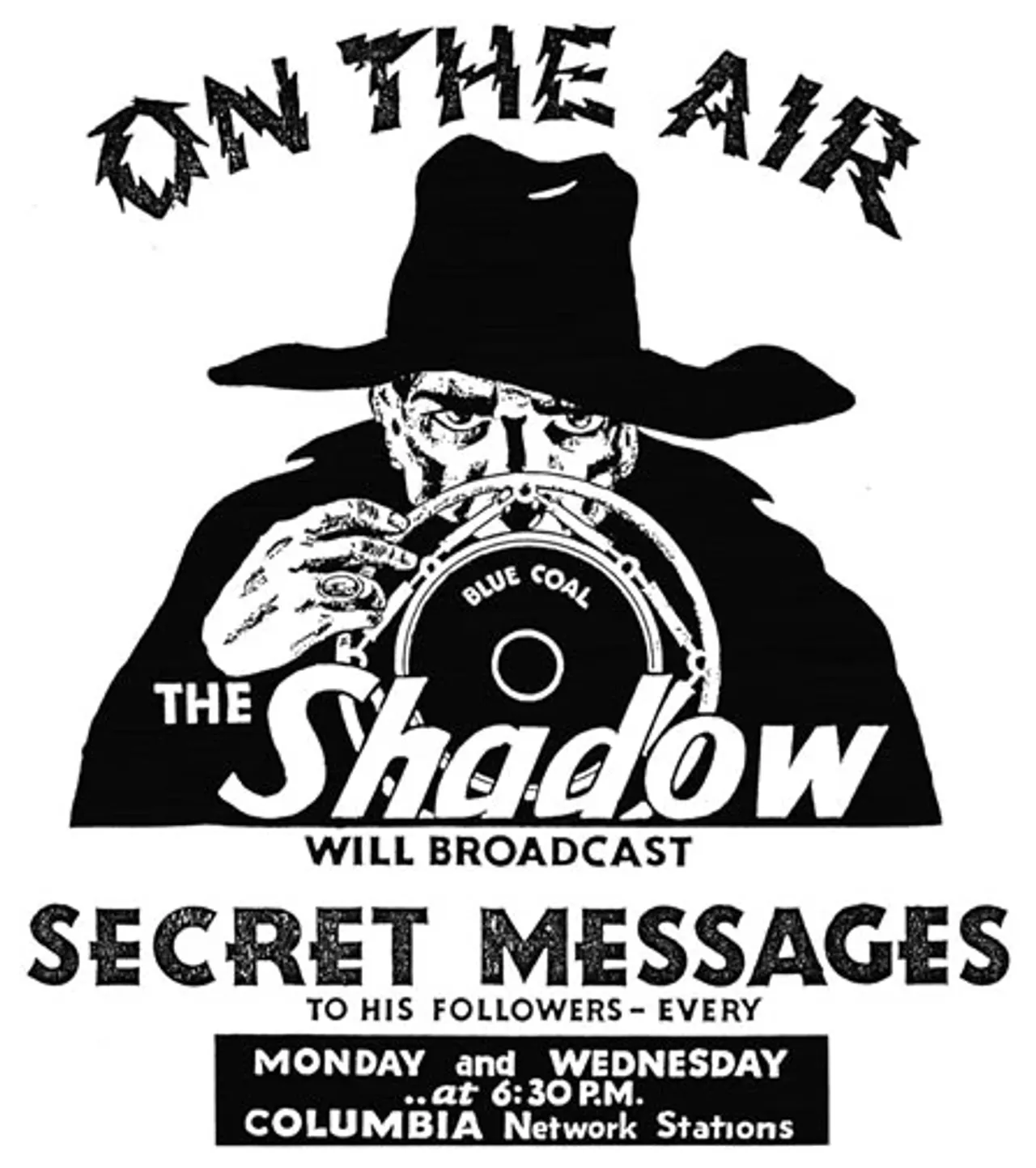

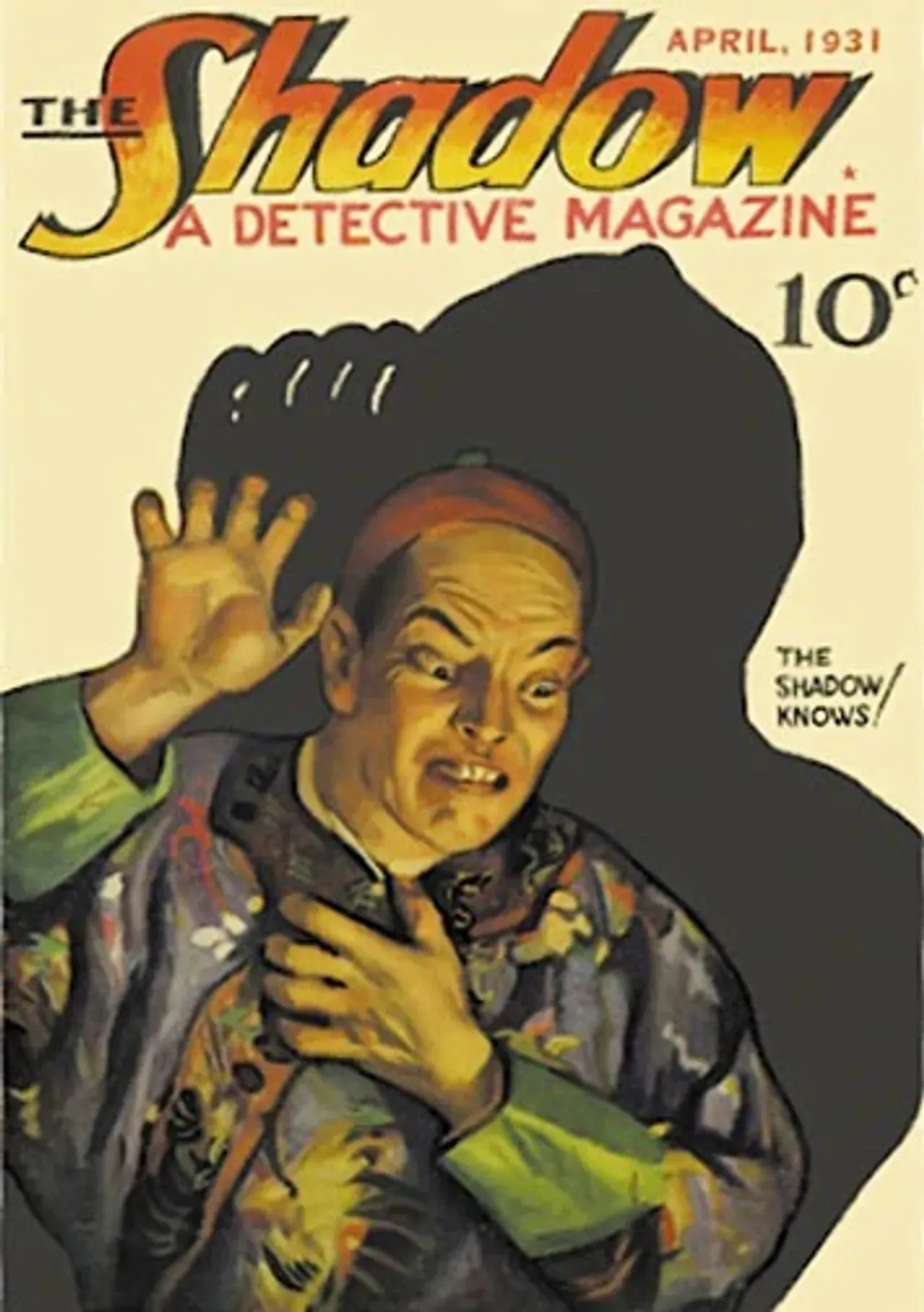

As the world of crime fiction evolved, radio and pulps gave rise to characters like The Shadow, who embodied a different kind of heroism. While Holmes operated with the utmost courtesy, The Shadow embraced the shadows themselves, navigating the darker aspects of society with a morally ambiguous flair. He took justice into his own hands, shrouded in mystery and often willing to bend the rules to achieve his aims. This shift from the analytical detective to the action-oriented vigilante showcased the genre's evolution, highlighting how storytelling could pivot problem-solving to a more visceral, thrilling approach.

The Shadow would make his debut on July 31, 1930 as a radio character but soon find additional success in his very own monthly magazine. The Shadow's alter ego had the classic detective setup: wealth, intelligence, and a knack for solving the most perplexing crimes. His appearance on paper was a natural extension of this enigmatic aura.

Walter B. Gibson, a writer and magician, was commissioned to begin writing stories about The Shadow following the initial success of the character. Gibson would go on to write 282 of the 325 tales over the next 20 years, producing a staggering volume of work to satisfy public demand. To put that in perspective, he was writing a novel-length story twice a month, penning upwards of 10,000 words a day. The Shadow cast a long and formidable presence, relentlessly pursuing justice while shrouded in mystery. He left an indelible mark on the collective imagination, laying the foundation for the evil that lurked in the hearts of men.

The Archetype: Vigilance

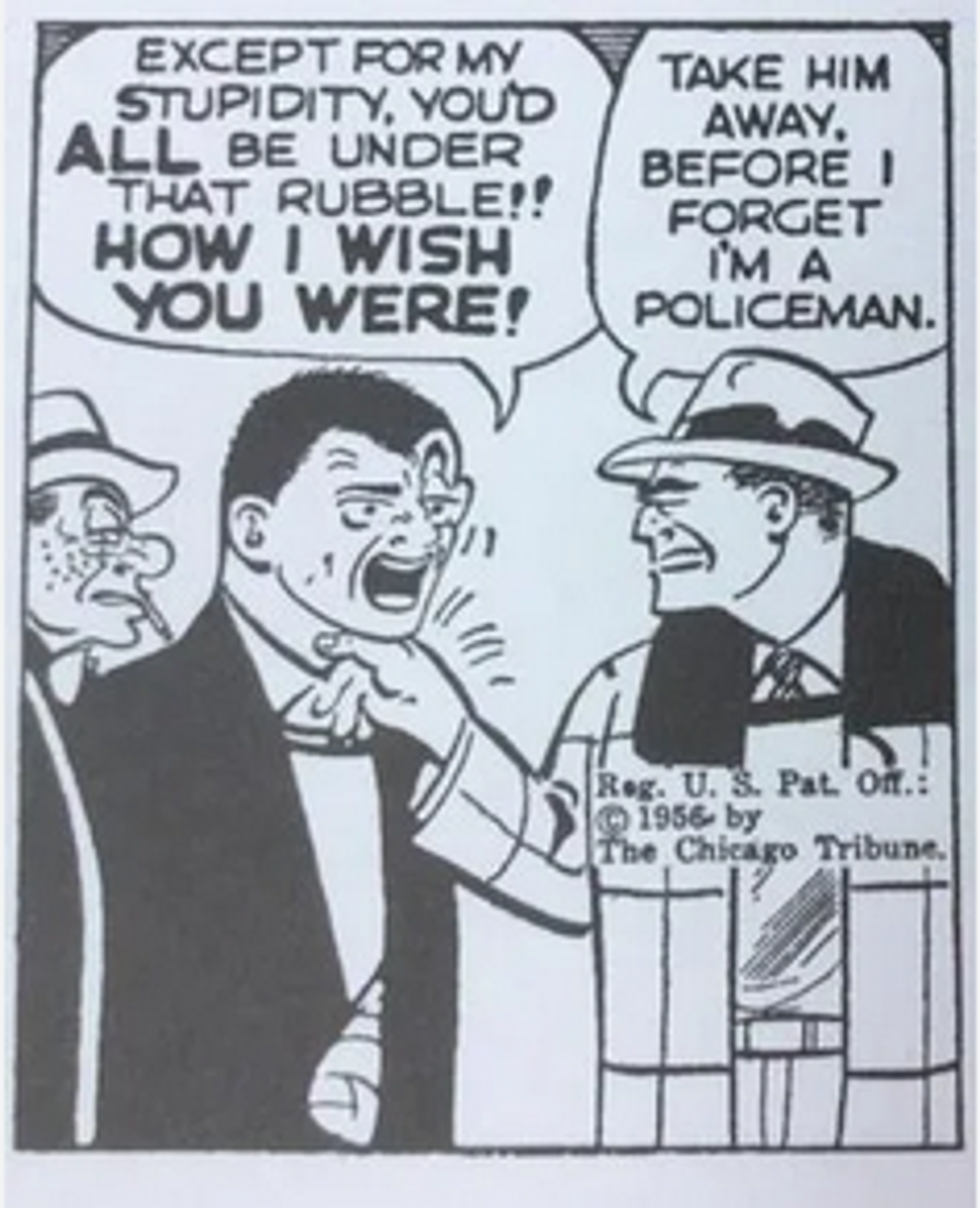

One year later, arguably the most hard-nosed detective to ever walk the beat was created by Chester Gould. Dick Tracy wasn’t just another gumshoe; he was a beacon of justice in a corrupt world, sporting a distinctive yellow trench coat and a square jaw that could break glass. Before pulps really took off, Tracy’s adventures were serialized almost strictly in newspapers, bringing crime-fighting straight into the homes of millions.

Dick Tracy’s early stories tackled issues like organized crime, drug trafficking, and the general battle against societal evils. Gould’s innovative use of gadgets and technology in Tracy’s cases made him a modern detective, blending realism with the fantastical. His unique style combined with bizarre and quirky villains set the tone for future crime stories, showing that even the most outrageous characters could be grounded in a gritty reality.

Then, and only then, as the city was steeped in it's darkest shadows and most whimsical intrigue, a defining icon was being forged in the crucible of crime—the one and only Bruce Wayne. Born from the same atmospheric grit that defined Dick Tracy and the pulps, Bruce Wayne emerged not just as a wealthy socialite, but as a dark avenger, wrestling with the demons of his past while patrolling Gotham’s ever-darkening streets. Rather than choose a side, Bruce Wayne as the Batman took the detective genre and embodied the struggle between light and dark, justice and vengeance, civilian and law enforcement. The essence of his character drew directly from the hard-boiled ethos, fusing the detective archetype with a personal quest that has resonated through decades of storytelling.

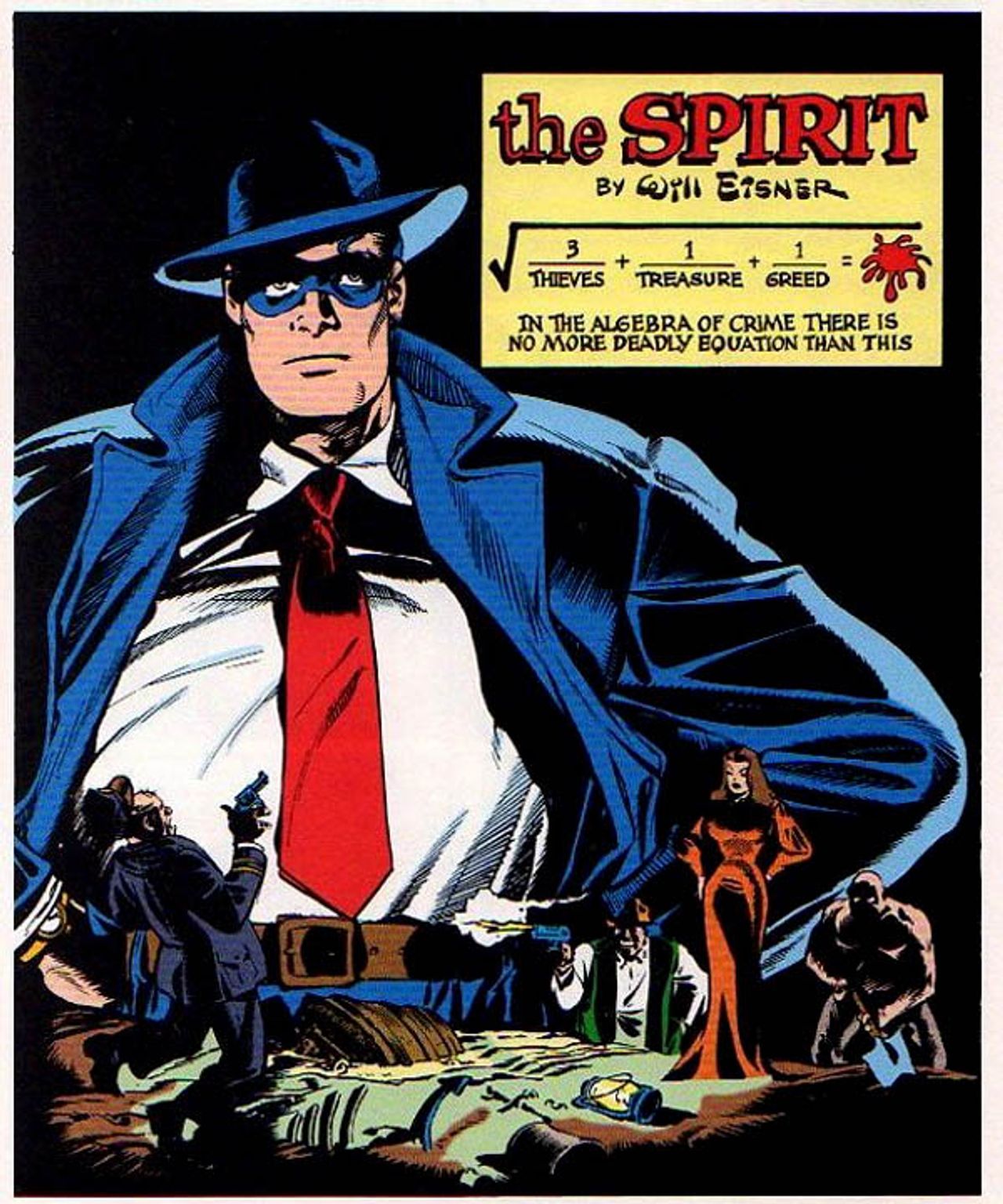

Coming full circle from the tenacity of the 30's, we enter into a spotlight for the genre, and quite suitably it is in the light that we make way for Will Eisner’s The Spirit—a hero who didn’t emerge from the shadows, but from a vibrant, cinematic playground where crime and comedy danced a delicate tango.

In mid-1940, Eisner unleashed Denny Colt, a masked avenger with a heart of gold and a knack for flipping the underworld on its head. Definitely not your average gumshoe; Denny was a suave operator equipped with sharp wits, the token well-tailored trench coat, and a penchant for cynical dialogue that could slice through tension like a well-aimed bullet.

Eisner’s innovation wasn’t just in his character now but in his storytelling as well. He painted intricate plots and moody cityscapes that somehow also captured the pulse of urban crime and corruption. The Spirit prowled Central City, a make-believe playground of misfits and crooks, with a strut and charm that set him apart from his contemporaries. His adventures were laced with witty repartee, a touch of the macabre, and a whole lot of chutzpah.

The success of The Spirit was no flash in the pan either. Eisner’s work truly laid the foundation for modern comic book storytelling, blending rich narrative with striking visuals in a way that had never been done before. The Spirit’s influence has rippled through the detective genre, setting a high bar for narrative depth and stylistic flair. As the world of comic books now began to evolve, Eisner’s creation remained a shining example of how detective stories could be both smart and sensational, low-brow and high class. Shoot first while simultaneously asking questions.

So, as you can see, the detective lifestyle has morphed and evolved over the years, picking up traits like a seasoned pro collecting clues along the way. It’s a symbiotic dance, the printed detective always shadowing the criminal mastermind, each reflecting the societal woes of their time. From the smoky, gritty days of pulp magazines to the vibrant, multi-layered storytelling of modern comics, the allure of the private eye remains a timeless one.

It’s not just about solving crimes; it’s about navigating the shadows of the human soul and emerging victorious, no matter the odds. Each sleuth brings their own flavor to the table—be it Holmes’s cerebral finesse, Tracy’s relentless justice, Bruce Wayne’s brooding duality, or The Spirit’s whimsical charm. In a world rife with darkness, these characters remind us that within the chaos, there’s always a flicker of hope. So tip your fedora, light that cigarette, and remember: in the end, it’s the journey through the shadows that makes the light worth chasing.